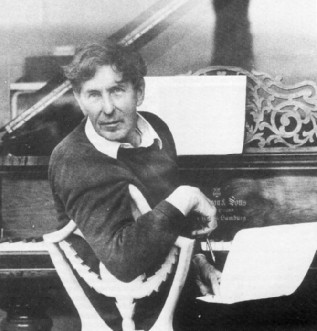

MEIRION BOWEN - Articles & Publications

An introduction to Tippettīs The Knot Garden

A few years back Sir Michael Tippett received a letter which read: "Dear Sir Michael, My wife and I recently moved to a house in the country. We should very much like to create a knot-garden there. We should be grateful if you could advise us, as we understand you are an expert on knot-gardens." Sir Michael replied, "I'm sorry but I can't help you, as the knot-gardens on which I am expert are entirely imaginary." That offers us our first clue to an understanding of Tippett's third opera (composed between 1965 and 1969 and first produced at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 1970). The knot-garden that forms the set is a dream-world conjured into existence at the very start of the work by Mangus, a psychiatrist. Comparing himself to Prospero in Shakespeare's The Tempest, he imagines he has the power to solve people's problems and set the world to rights. The knot-garden is thus a magic place, like the island in The Tempest (or for that matter the magic wood in Tippett's first opera, The Midsummer Marriage). At the point in Act 3, where Mangus realises he doesn't have such powers, that "Prospero's a fake... this island's due to sink into the sea", the knot-garden briefly disappears from view. In the course of the opera, the knot-garden has different functions indicated by the titles Tippett has given to each act.

Act I is called Confrontation: here the knot-garden is simply the place to which Mangus has brought six people whose relationships are in disarray. The most important of them are Faber and Thea, husband and wife, whose marriage is at breaking-point. He is preoccupied with his business affairs, his factory papers; she withdraws to the dream-world of the garden. Their ward, Flora, has as much difficulty coping with the problems of adolescence as in dealing with the tenstions between her foster-parents. Two of their friends appear, Mel (a black writer) and Dov (a white musician). Their relationship (whose nature I cannot disclose under Clause 28 of the Local Government Bill) is also on the rocks. Lastly, there is Denise, Thea's sister. She stands apart from all these psychological problems. She belongs to the world of political protest and freedom-fighting. Her scarred countenance and declamatory rhetoric add a special dimension to the drama, and throughout one realises that she is a catalyst to the action.

Act II is entitled Labyrinth: the knot-garden is transformed into a maze, so manipulated by Mangus that the characters constantly interact in different pairings, but are drawn away again when their encounters attain a climax of possible violence or love. In Act II, called Charade it is the scene for a series of games or charades aimed at achieving self-awareness and reconciliation amongst these disparate personalities.

Tippett's operas are steeped in allusions to other theatrical works, and in The Knot Garden it is quite easy to find connections with Shaw's Heartbreak House or Mozart's Cosi van tutte (where, also, the characters tend to appear mainly in twos and threes rather than singing separate arias). But the most important reference-point is undoubtedly The Tempest, and in reading the libretto (which, as usual, Tippett wrote himself) and following the performance in the opera-house, it is worthwhile keeping Shakespeare's play in mind.

The Knot Garden begins with a "storm" prelude, just like that in The Tempest a psychological rather than an actual storm, a device for bringing all the characters together in one place, an island in the play, a knot-garden in the opera. Then, some of Tippett's characters are modelled on Shakespearean prototypes: Mangus dreams he is Prospero; Faber is a recreation of Ferdinand; Flora, Miranda; and Mel and Dov, Caliban and Ariel. In the charades they play together in Act 3, they revert to their Shakespearean prototypes: and when they are on the brink of resolving their problems, Tippett quotes his own setting of Areil's song, "Come unto these yellow sands" (written for an Old Vic Theatre production of The Tempest in 1961).

If The Tempest is the main link with past theatrical tradition in The Knot Garden, the techniques of television, cinema and the twentieth-century popular musical are used to ensure a sense of immediacy and modernity.

The action often moves at the sort of pace more generally experienced with TV or cinematic presentations. Instead of cumbersome transitions between scenes, Tippett has written a 16-bar Allegro molto passage, which recurs throughout as the gesture for a quick scene-change: purely functional music, this, intended to blot out what has just happened and take us into new territory dramatic and musical as swiftly as possible.

The Knot Garden is built out of a mosaic of little blocks of music leitmotifs which remain in the memory because their scoring is never changed (e.g. Thea's motif is always scored for three horns and high strings). Examined in detail, they are mostly little song-and-dance routines, entirely apposite to an opera in which the characters are constantly acting out dreams and fantasies. Sometimes these are built into big song-and-dance numbers, such as the scene between Mel and Dov in Act 2, or the slow blues and fast, up-tempo boogie which form the basis of the final ensemble of confrontation in Act 1.

More fundamentally, dance is the most important metaphor in the opera. When the characters line up together at the climax of Act 3 and join hands in an expression of reconciliation, Tippett's libretto quotes from a poem by Goethe, Die magisches Netz, which depicts the comings and goings of a group of people dancing with a net:

"We sense the magic net That holds us veined Each to each to all".

The "storm" prelude at the start of Act I is thus really an angular, distorted dance which keeps breaking down and starting up again. This music recurs in Act 2, linking the different pairings-off of characters in the labyrinth: and at the end of the opera, when Thea and Faber have reached the stage where they might once more communicate, the storm-motif, slowed down, goes into reverse and finally gathers all its notes together into a final sweep of harmony.

Knowing that The Knot Garden is anchored in The Tempest, and being aware of the use of dance imagery, literal and metaphorical, are two essential life-lines for the opera-goer attending a performance for the first time. But it is also worth being aware of the overall shape to the piece. Up until about two-thirds of the way through, it appears that everyone is in turmoil. But then, the two most innocent figures in the opera, Dov and Flora are suddenly flung together in the maze. This is the turning-point of the work: now one realises that things might possibly go right for a change.

Dov comforts Flora and persuades her to sing. In her immaturity, in her inability to connect with the modern world she inhabits, she can only retreat into the past world of Schubert and what she sings is also a boy's song. Dov counters with a song of his own, a modern-style piece, with electric guitar and throbbing pop-style rhythms, in which he tells of his boyhood in the big cities and dreams of love in the warm Californian West. Suddenly, the knot-garden flowers into a rose-garden (in Persian mythology, a knot-garden was a rose-garden where lovers met). From now on in the opera, there is some likelihood that the tensions that divide everyone will be resolved. Not completely, of course: that would be pie-in-the-sky, untrue to life. At the end, Flora has attained some degree of self-knowledge, and leaves, "radiant, dancing". Mel and Denise find common ground in their concern for civil rights, though she is uneasy about his (currently unmentionable) sexual inclinations. Dov leaves on his own, an object of pity. He is the artist and loner who has to search for his vocation in the world. (Identifying with him, Tippett subsequently wrote a song-cycle, Songs for Dov, concerned with his future travels in pursuit of creative maturity.) Lastly, Faber "puts away the factory papers" and Thea "puts away the seed packets", their enmity "transcended in desire". As the curtain falls in the opera, it rises in their lives.

The special dimension offered by the presence of Denise is a connection with the world outside the garden, the world of the city. She ensures that the opera does not simply become cosily introverted and precious. Thus it is ultimately about the real world, and as much about reconciliation of opposites in human as individuals and in whole societies as Tippett's oratorio A Child of Our Time and The Midsummer Marriage. The fact that there is a city beyond the garden, also affects the music. Tippett had just visited America for the first time when he began writing the opera. Its extremes of climate and geography, and its polyglot culture affected him deeply: he referred to it as, for himself, "a new foundland of the spirit". In The Knot Garden, his music thus became overtly free-ranging and pluralistic in idiom, manifesting a richness of colour, rhythm and harmony commensurate with his subject.

The'Knot Garden is an intimate opera, with just the seven characters, no chorus and the action happening within the course of a single day. And yet as Sir Peter Hall's first production demonstrated it can make its mark equally well in a large theatre like Covent Garden, with full orchestration, as in smaller venues, with my own reducing scoring (involving only 22 players). Above all, it is a theatrical entertainment, cleverly paced and full of surprising twists and turns. To my mind, it is the best of his operas so far, with the most concise and telling libretto and sharply imagined music.

Top