MEIRION BOWEN - Articles & Publications

Variation Forms

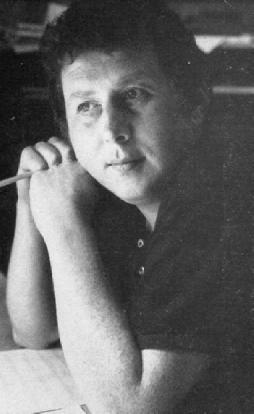

HARRISON BIRTWISTLE LIVES in Twickenham and composes in a gazebo-like place at the bottom of his garden. He is not a recluse. Neither is he an exhibitionist, let alone a hair-brained anarchist, hell-bent on blowing his and our minds. With every year that passes he strengthens his position in the forefront of contemporary music. To do so needs considerable integrity, for these days one can make a name for oneself quickly by joining the Stockhausen or Cage caravan, going on the multi-media rampage, picking up the Scratch epidemic, or selling out to the computer or films. Birtwistle takes stock of it all, and accommodates what is consistent with his own way of thinking.

He is by no means the purveyor of a narrowly delimited area of musical experience. Far from it. The most cursory acquaintance with his output over the last twelve years or so would reveal a decisive broadening of scope and an increased complexity joined to greater lucidity and assurance in handling his chosen medium. This is especially true in the period since he wrote Tragoedia (1965). Robert Henderson, writing in March 1964 (Musical Times), discovered in Birtwistle's music in general 'a certain gentleness of feeling, an absence of any unduly emphatic gestures'. Little did he know that the composer was on the verge of a foray into musical territory of a savage violence and corrosive power, such as would eventually drive the Aldeburgh opera patrons from their seats in the Jubilee Hall in terror. With Birtwistle an elusive unsensational untemperamental figure, you can be certain that he knew what he was doing.

The stockily built Birtwistle lived his early life on an Accrington farm (where he was born in 1934) and his musical talent was immediately manifested when, at the age of seven, he acquired a clarinet. He started composing immediately, and continued doing so into his teenage years, despite a lack of musical education (for which collective renderings of well known songs in the school classroom were no substitute). A scholarship to the Royal Manehester College of Music, where he studied with Richard Hall, brought him musical training of a kind that he felt alien to him. Composition studies were to such a degree based on what he calls the 'goal-orientated' tradition of European music, that his creative vitality was numbed.

At this stage he virtually stopped composing and concentrated on clarinet studies and on performance in general. He met Alexander Goehr and Peter Maxwell Davies. Together they formed the Manchester New Music Group, which played a wide repertoire of contemporary music of the sort you would hardly hear in London at the time (around 1953), let alone in Manchester: Messiaen, Berg, Webern etc were all featured. Birtwistle then spent two years in the Army. Afterwards while (nominally) a clarinet student at the Royal Academy of Music, he started composing again with a vengeance.

As a child it was his fascination with the raw materials of music, with sound itself, that underlay his compositional urge. This same fascination led him back now as an adult to creative work. His identity as a composer has always been strongly felt. Subsequently, several years as a teacher by no means altered his stance. Nor did he acquire an American accent or habits while in the USA on a Harkness fellowship (1966-68). He remains true to himself and to his upbringing.

Birtwistle has always started from first principles, from the very nature of the forces employed, and their sound potential. His concepts of musical structure derive from no single tradition but from natural forms, forms that are efflorescent in themselves. Birtwistle will begin from single notes, or elementary motifs which then grow out in all directions, expand, contract, grow new thematic branches, shed subsidiary material and so on. His musical fingerprints are quite basic. He has always been obsessed with the possibilities of repetition, the single developing line, above all symmetry. The sources of these particular obsessions are, on the other hand, quite diversified. They comprise a vast body of experience and observation, some of it explicitly stated, some of it implicit but not necessarily deducible.

You might in his case formulate a relationship between such sources and their end products along lines comparable to, say, Klee's theories and practice. With both artists of course it is the end product that counts: Klee's vast compendium of speculation and perceptual analysis contains inconsistencies and errors which you can ignore in evaluating the drawings etc that sprang from them; so, with Birtwistle. you should think in terms of the intrinsic worth of his music. while allowing due place to the consideration of sources and intentions, which are of course quite essential to an understanding of the composer. While many have come to terms with individual works of his and there has been a profusion of them, some lengthy too, over the last six years or so few have formed a total picture of his musical personality.

Birtwistle's first published work, Refrains and Choruses for wind quintet (1957), at once reveals his fascination with verse forms, a feature of all his music. Its origin lies not so much in any specific interest in early music, as in the archety- pal nature of the form itself. For Birtwistle music by its very essence exists in a time-continuum, and therefore must have a beginning and an end. Composer and listener become aware of 'modes of change' in the sound-material deployed within that continuum. Repetition is one means whereby these modes of change attain coherence. The verse-form in Refrains and Choruses is rather freely treated: the four sections of the piece are closely interwoven, losing some of their aural distinctiveness thereby. In later works where the thematic units are generally much smaller the sections then proliferate, taking in a wide gamut of sonority and texture, and the repeating forms are more tautly organised. Repetition has become but one method of giving the music a focal point within a multiplicity of changing patterns.

Had he not been a musician, Birtwistle must surely have been a painter or a sculptor. His music throws up far more analogies with the visual arts than with the kind of literary references that come to mind in connection with most Euro- pean music since the time of Beethoven. Instead of dramatically conceived music that moves forward inexorably and in- evitably towards some particular goal or apotheosis, we find with Birtwistle a sound-conception more comparable to, say, mobile sculpture or film. We are concerned in musical terms with relationships between geometric shapes and planes as observed from different angles or in transition from one set of perspectives to another. Thus few of his major works need be thought of as untouchable finished enitities. They tend to be open-ended, capable of further change or elaboration.

Birtwistle has revised some compositions simply by extending them. Medusa, for instance, grew considerably between its BBC premiere (November 1969) and its first live London performance (Mareh 1970). Nomos (1968) is amongst those works which have not seemed entirely suecessful, and the composer's cure would be purely that of expansion. Entr'actes and Sappho Fragments developed from a small-scale conception (1962) into something much more substantial (1965); it will be considered in more detail. Moreover each piece seems to imply another. Birtwistle's opera, Punch and Judy (1966-67) grew naturally from his Tragoedia (1965).

His ultimate reference point is the original source of the music itself: hence his habit of beginning from a single note or phrase, or placing a single line melody in the foreground. Constantly he asks the question, why sing or play? To that extent his creative ambitions run parallel to Tippett's, though they are completely independent by nature. And as with Tippett also his musie tries to provide an answer. In Monody for Covpus Christi (1959), for instance, the soprano line at first plays with inflexions of the word lully against fairly non-committal single-note interjections on horn. Then, starting with the flute, the other instruments, horn and violin, gradually join in, continuing on their own when the voice drops out. With successive couplets of the poem, the music generates pace and thematic movement; after a climax is reached, it is left to the flute to accompany the voice almost to the end of the first seetion, highlighting the words Corpus Christi with long single notes surrounded by a halo of ornament, and a separate quasi parlando treatment of the words 'written thereon'. This difference of emphasis marks the expressive connection between words and music explored throughout Birtwistle's work.

Ring a dumb carillon (1965) this month's music supplent takes this relationship between words and music further, and in so doing, exemplifies more vividly the raison d'etre for music-making which the composer is suggesting. In this setting of a text by Christopher Logue, we can see the emergence of a corporeal as opposed to abstract notion of creation. That is to say, the act of creation is the product, primarily of a physical need, secondarily of objective cerebral pattern making. The interplay of voice and accompaniment here bear upon this issue. The piece starts with single notes for voice and clarinet, with the intervallic elements that are the seed of the whole piece soon introduced. At first the percussion fills a subordinate role, providing mere punctuation. Then as the piece gets under way there is more integration of voice and percussion, while the clarinet ruminates rather on its own enjoying cadenza-like freedom. The music subsides to nothing and starts again in a similar manner, gathering momentum to a point where even the soprano herself starts playing, on suspended cymbals. This is the final rolationship that prevails one of total involvement.

Music, Birtwistle seems to be saying, springs from within ourselves as vital physical organisms, and from our speech inflexions. This is the deepest source, whether its outward manifestation be vocal, instrumental or theatrical. Whatever medium Birtwistle has handled, his approach has remained the same: he must return to the raison d'etre of that medium as his starting point.

In his first big orchestral work Chorales (1962-3) for instance the various blocks of sonority are at the start built around a solo violin melody. They then assume greater independence, but still converge to produce a monophonic flow of music. The original solo line reasserts itself, this time on horn, but now can give rise to the succession of rhythmically elaborate chorales on various groups of instruments whioh are the focal point of the piece.

It is likely that Birtwistle's obsession with the single melodic line as the source of his music will figure even more prominently in forthcoming compositions. His most recent work that I have heard, The Death of Orpheus(1970), is partially a study for his next opera. Whilst ritual has always interested Birtwistle, here for the first time he concentrates on a specific myth, one that bears on his own quest for the motives behind creation. The Death of Orpheus is modelled on the Nenia (this is part of the work's full title) or ancient Roman funeral song (also the name of the goddess invoked on such occasions): a dirge that runs the full gamut of vocalisations from separated spoken monosyllables building towards more elaborate melismata. To highlight the important words, Euridice and Orpheus, Birtwistle uses long single notes. Orpheus' distinctive attribute in life was his eloquence as a singer. This is reinvoked. The soprano line separates itself from the dark-textured, winding accompaniment of bass-clarinets and crotales at the crucial points in the text.

That Birtwistle should be drawn to the Orpheus legend coincides with his current long-term absorption with another opera, for Covent Garden production. Whereas Boulez has decreed that opera-houses should be blown up, Birtwistle will, in effect, hope to justify their survival. His opera, based on the myth of Chronos, will portray the primaeval Chaos out of which is born the human species that discovers the need to sing. We shall see this progress from a dumb show to singing as part of the stage action. Birtwistle believes his own primary task as a composer of opera is to explain how it is that characters need to sing, instead of merely speaking or whatever.

Alongside these investigations into the root-sources of music-making, there is Birtwistle's search for underlying formal archetypes, something which has shaped his own musical ideas as well as determining his large-scale strategy. Three composers have exerted an influence upon him that he would himself recognise: Messiaen, whose block-scoring he emulates, but takes further afield; late Stravinsky, whose alertness to the quality of intervallic elements he shares; Mozart, to whose lucidity he aspires.

To my mind his work as a whole seems to bear closer comparison with that of Edgard Varese. Both started from an examination of the premises of all musical thinking. Varese in Ameriques and Arcana was marginally less successful in articulating his ideas in full orchestral garb than he was with smaller, more select ensembles in Octandre or Integrales. Like-wise with Birtwistle: Chorales is far less assured indeed suffers from orchestral elephantiasis than say Tragoedia, or Entractes and Sappho Fragments. Both moved towards the discovery of the potential of electronically produced sound, musique concrete etc. Varese took his structural models from observed nature crystal-formation for example and this is one type of approach for Birtwistle also.

Such is the case, for instance, with Birtwistle's Medusa (1969), whose title refers not only to the Greek myth of the Gorgon's head, but more importantly to a species of jelly-fish that has eight identical parts, each of which is a microcosm of the whole. The jellyfish reproduces itself not by fertilisation but by detaching one oart, which then grows into a fully-matured jellyfish. Birtwistle draws this analogy because likewise, Medusa contains musical matenial that can continue in relation to the whole or can divorce itself, lead an independent life of its own, or disappear altogether. Such a process is commonly found in Birtwistle's music: here amplification and electronics give it extra scope. Medusa employs two tapes: one a recording of a distorted saxophone sound; the other synthesized sounds. It also involves an electronic instrument (performed by the keyboard player that extends the percussion sound. The spectrum of colour in Medusa is thus vast. It is superbly manipulated in a for: whose enormous ternary shape is reflected in the large number of small segments which it comprises.

The wistful opening clarinet motiif reappears at various points in the work, and is a powerful foreground motif in the final sectrion. Yet it is just one of many such motifs heard throughout the composition which relate to each other like the several planes of some complex geomctric artefac: Each block of musical material seems cayable of existing within its own time-continuum, whiile two or more that start together can go out of phase. Most striking in this respec. is the use of a Bach chorale, which is subjected to a multiplicity of melodic, rhythmic and harmonic distortions.

Birtwistle's main output as a composer, however, has been nourished by exploration of the formal characteristics or verse forms and their extension within the larger framework of Greek drama. Early evidence of this is found in Entr'actes and Sappho Fragments. This started as a set of pieces for flute, viola and harp, A Song book for instruments (1962) which comprises entr'actes 1, 2, 3, 5 and the coda of set 1 of the final structure. Entr'acte 4 was inserted the following year. By the tirne of its publication (1965) the work had grown into its present form with a second set. This increased the ensemble by including an oboe, violin and percussion, as well as a soprano. Interwoven here with variants of the entr'actes are settings of fragmentary lyrics by Sappho - Canti - finishing with a vaniant of the Coda. From those entr'actes that do not reappear (nos 1 and 4) Birtwistle lifts certain seminal motifs for quotation in the vocal movements.

The musical material is treated thus as a collection of 'found objects', and this is a recurring facet of his music thereafter. The appearance of a Bach chorale in Medusa, for example, makes an unusual impact, for it is treated as another 'found object', just like the rest of Birtwistle's thematic ideas. This characteristic of his musical thinking enabled him to move into the sphere of electronics, musique concrete and so on, without much diffiaulty.

With Tragoedia (1965) Birtwistle moved decisively towards an overtly dramatic organiisation of his music. It was a turning point in his development, for it brought about a refinement of the slightly more amorphous forms and textures of his earlier works. Here he created an instrumental work of a deliberately dramatic nature, givung each movement each section of a movement a title from some formal feature of Greek drama. The title does not imply a tragedy in the modern sense, but refers only to the origins of the headings for each movement; literally Tragoedia means 'goat-dance'.

It is worth considering the piece alongside Punch and Judy, for which it was a study. With both the scoring is an element of great significance in establishing the intended theatrical effect. Tragoedia employs two groups of instruments wind quintet and string quartet which are linked a.nd fused by mean,s of a third force, a harp. Punch and Judy makes extensive use of a stage ensemble (wind quintet) and pit band (strings, trumpet, trombone, harp, percussion).

Both works are in essence studies in bilateral symmetry, wherein the structural layout and scoring lend force to each other. In Tragoedia, the Prologue stands outside the work proper, as a soparate piece of symmetry. The core of the piece is contained in two movernents entitled Episodion. These are separated by a Stasimon, introduced by a Parados and followed finally by an Exodos. In the first Episodion (itself divided bilaterally into Strophe-Anapaest-Antistrophe) two types of texture are contrasted: solo versus group in the outer subsections (horn against strings, then cello against wind), and the two soloists together in the middle section. Episodion 2 reverses the character of the sub-sections of Episedion 1, but re-arranges their scoring and content more freely. Moreover, in the central Anapaest of Episodion I, the Antistrophe of We have here a gesture of the same order as that in Ring a Dumb Carillon where the soprano plays suspended cymbals symbolising the yerformer's physical involve- ment in the instrumental drama. The harp has a mediatory role in the symmetry of the scoring, and this is most ap parent in the Stasimon separating the two Episodions. The harp figure that closes the Parados recurs in Episodion 2, and ends the whole work; it is one of the few actual quotations from Tragoedia (see page 36) traceable in Punch and Judy.

In the opera, a simiilar set-up prevails: the larger symmetries contain much smaller symmetries or departures from symmetry; the great fleas have little Reas, as it were. Again, the orchestration is an in,tegral part of the structure. Punch and Judy has its own Prologue and Epilogue, and is organised into four Melodramas, each corresponding to a murder. A Nightmare episode interrupts the third of these. Each Melodrama contains a sequence of short sections that precede the music for the actual slaughter a complex of events that is varied each time it recurs (as compared to the earlier music which is generally non-recurrent). After each Murder sequence, Punch sets off in search of Pretty Polly. Here again we have a verse cycle, consisting of varied and repeated elements; the Nightmare breaks the force of repetition by displacing this in the third Melodrama.

Birtwistle's instrumentation articulates these variations on symmetrical patterns. Not merly do the yit and stage en- sembles set up contrasts and come together to envelop the dramatiic action, as it were; but from them issue forth the typical thematic blocks, ostinato figurations, repeated netes, chords, and so on, that are the opera's expressive substance. The violent repeated notes of the Parados and Exodos in Tragoedia recur in Punch's war-cry (page 8 of the vocal score), making what was once a mannerism in Birtwistle's early musical idiom a telling quality. And this is but a single instance. The two works share a pungency and violence that ispring from the composer's comparatively recent fondncss for sending the wind instruments up into their highest registers.

As in Tragoedia also, the more lyrical episodes such as Judy'is 'Be silent, strings of any heart' and the final love duet have a rhythmic mobility that is novel and refreshing.

Just as Birtwistle eschewed referenee to any specific myth in Tragoedia, with Punch and Judy he tried to create a sort of open-ended opera a 'source' opera based on one of the oldest of istage-legends. The allegory of Punch and Judy must lie close to this composer, for Punch represents man in search of his own identity: his successive murders a ritualistic portrayal of his abandonment of convenitional per- sonal psychological, and soaial ties. Pretty Polly, whom he ultimately attains, stands for his goal of self-integration. Stephen Pruslin's libretto for the opera rather confused the issue with suggestions of other interpretations (eg political) whiich are not essential within Birtwistle's terms of reference: quite apart from the indiscriminate compilation of riddles, puns, cryptic statements etc that befuddle the actual narrative flow. A lot of people were relieved that Birtwistle's noisy dissonanit music drowned so many of the words. As in Tragoedia, there are conAicting forces in Punch and Judy, and an outside mediatory/commentatory element, here the combined voices of Doctor, Lawyer etc and above a Choregos. Choregos is both showman-commentator and the alter-ego of Punch himself. In truth Choregos represents music itself. In a Coronation scene he is crowned with trumpet, drum and cymbals (the tools of his trade), only to be bowed (or sawed) to death later as he sits inside a bass viol. This rejection by Punch even of his own better qualities signifies the full extent to which he is prepared to go to assume his most distinctive identity.

Birtwistle's success with this opera was the fruit of a number of early voyages into the territory of drama, but considered from the angle of its cssential funationing in musical terms. His association with the Pierrot Players which he co-directed with Peter Maxwell Davies until the group disbanded in 1970 may prove to have been a cul de sac in his creative career, even though he had here further scope for dramatic experiment. The limitation of the group to the sort of ensemble Schoenberg had employed in Pierrot Lunaire was rather restrictive. It presupposed a kind of expressionistic texture and form of utterance which were irrelevant to Birtwistle.

For the Pierrot Players' first concert in 1967, he wrote Monodrama, whose staging was a disaster, however many worthwhile opportunities it aKorded. Again we find here an odd conAation of expressionistic and classical dramatic forms: a sort of source book for drama. It was suggested by an early form of Greek tragedy in which a single actor took on numerous functions. The soprano protagonist passes through a prodigious range of vocalisations, from speech to melodramatic singing. As in Punch and Judy, there is a Choregos combining the functions of alter ego to the protagonist and outside chorus. But the music rarely gets off the ground: the four Interstices contairn the most impressive musical episodes.

The task of providing a repertoire for the Pierrot Players involved Birtwistle in further projects on a smallish scale, of which the most enduring is the Cantata (1968). For this Birtwistle himself eompilcd a text from tombstone inseriptions and free translations from Sappho and a Greek anthology. Furthermore we meet here a theme that harks back to early yhases of his career: regeneration. It is the central concern in the unaccompanied choral work Narration: The description of the passing of the year (1964); also in Punch's quest to east and north, south and west in the opera; and in the dramatic pastoral, Down by the Greenwood Side (1968). The Cantata occasioned further multi-layered musical material deployed in such a way as to integrate with the vocal line.

Other contributions to the Pierrot Players' repertoire are arrangements of late mediaeval or early renaissance motets and chansons by Ockeghem, Machaut and others. These are not of primary importance to Birtwistle certainly not to the extent that this type of work has been to Peter Maxwell Davies. On the other hand, he had much earlier, in The World is Discovered (1960), produced a set of six instrumental movements, the offshoot of a canzonet by Heinrich Isaac. This is very much an independent composition, an early instance of his employment of verse form a distinct improvement in fact upon his Refrains and Choruses. The fact is that Birtwistle is at his most idiosyncratic when he has moved away from his models: or rather, far enough to be able to re-introduce them as 'found objects' like the Bach chorale in Medusa, or the old dance forms (gavotte, allemand etc) that occur in Punch and Judy.

This sense of freedom from a prescribed model ha.s seemed far more possible within the context of the Music Theatre Ensemble (founded by Alexander Goehr). For this group Birtwistle wrote Down by the Greenwood Side (commissioned by Ian Hunter for the 1969 Brighton Festival), with a libretto derived from mummers' plays by Michael Nyman, which efFectively combines all the best bits from the originals. Some of the themes here form links with previous pieces: for instance, child-murder, re-invoked from Punch and Judy (though for B,irtwistle it dates back to the first film he ever saw, Alexander Nevsky, iwhose opening image of children ,being thrown into a fire he has never forgotten!); and re-generation and rebirth, which eomprise the main body of the work. The piece is sufficiently well planned to allow the contrast between Mrs Green's lyrical music and the violent, black pantomime elements to make itself felt.

It is not that Birtwistle's involvement with the Pierrot Players was unproductive. But apart from the Cantata and Medusa most of his music for them has either been on a small scale, or has continued compositional processes that were in the offing before the group was formed. This is true of Verses for elarinet and piano; Linoi I, for clarinet and tape (later revamiped as Linoi II with a largely gratuitous dance element); and Four Interludes for a Tragedy for clarinet and tape especially composed to provide a framework for a continuous programme (Spring Song at the Elizabeth Hall in March 1970).

It is in keeping with his keen sense of future artistic objectives that Birtwistle should reject any artificial strait-jacket on his creative expression. While a teacher he produced the vast quantity of Gebrauchsmusik, incidental music to plays and so on, which should be the stock-in-trade of any musical educator, but regards none of it as of great importance to the world at large. He has demonstrated, on the contrary, that school music can be lifted to a much more elevated plane of aehievement; eg the ingratiating Music for Sleep, or The Mark of the Goat, or more significant The Visions of Francesco Petrarca.

This last was a large-scale work and, like most of school compositions, cairries the,imprint of his other music: it contrasts settings of Petrarch sonnets (in Spenser's translation) for baritone solo and chamber orchestra with the same mimed to music by the full o,rchestra: the verse form in a new guise. Birtwistle's instrumental writing here harnesses the virtuosity of young performers to a yartieularly notable percussion ingredient in the scoring (including anvils and metal tubes).

Of his most recent works, none perhaps defines more clearly his identity, or indicates his future horizons so surely, as Verses and Ensembles (1969). This does not have the overt references to Greek drama that we find in Tragoedia and other pieces. But there is a theatrical disposition of the twelve players, who are subdivided into smaller self-contained groups clearly articulated in relation to their musical material and function, and spatial distribution; there are seven playing positions in all. Yet the separation of the groups, in distinctive antiphonal writing, solo outbursts or interventions for example, are only the surface indications of another of Birtwistle's elaborately seulptural groundplans.

On one level, one can consider its thematic structure. The starting and finishing points are two pairs of articulated notes, for horn with oboe or two trumpets respectively which recur to initiate activity at any point, and are finally resolved into an AED chord on the final rising accelerando. Within the framework of a series of eharacteristic interchanging and colliding blocks of thematic material there are cadenzas, or solo interruptions, which take the music on to a diferent geometric plane: an idea which the performing lay-out aceentuates. The two trumpets intervene from their stereo-style separated positions at one such point in the midst of antiphonal exchanges. Elements of repetition canons, ritornelli, verse-forms proliferate in this work. And the procedures acquire a further dimension by the use of aleatory elements in the notation, which are not a substitute for invention, but a means of increasing the range of geometric shapes the material undergoes.

Birtwistle is largely out of symyathy with avantgarde experiments with notation which leave too much to chance. His aleatory writing here and elsewhere (eg in The Death of Orpheus) has a fixed artistic objective. This is the norm with everything Birtwistle attempts. He is an empirieist like Varese: yet with a strong intuition as to what he is after. In a country that has produced countless musical Peter Pans, Birtwistle already looms large in stature.

Top